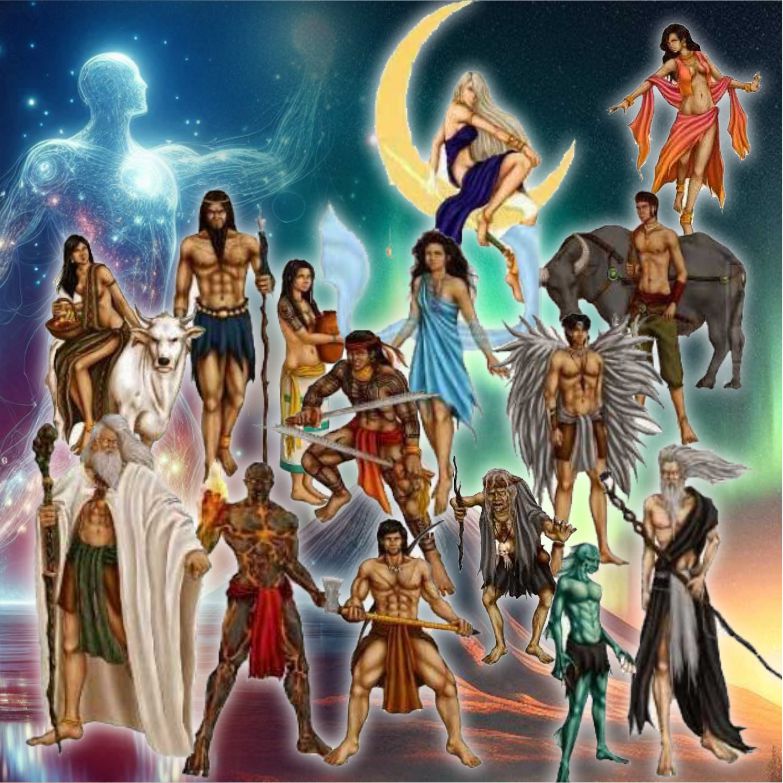

The Ancient Gods in Philippine Mythology

Long before the arrival of Magellan and Christianity, or the spread of Islam from Mindanao a hundred-fifty years earlier, the inhabitants of the Philippine Islands already had varying forms of religion and deities they worshiped. Back then, the Philippines wasn’t a unified country as it is now. It was a collection of tribes, ethnic groups, and small kingdoms with different cultures, practices, and beliefs.

Just like other cultures from around the world who created their own gods and other divinities, so did the ancient Filipinos. Having reached a point in their cultural development where they were curious about the world around them, they needed a means to explain how things came to be, as well as a template to base their cultural beliefs and sense of morality on. Thus, the belief in spirits, deities, the afterlife, and other realms was born.

The Gods, aka Diwata

One of the common beliefs shared by pre-colonial Filipinos was the worship of spirits and the invisible, otherwise known as Animism. These spirits are known by many names in different languages. Some of the ancient Visayans called them the umalagad; in Mindanao, they are called the dewa. But for most, and as they are most commonly known to this day, these spirits are called the diwata (a name of Sanskrit origin).

The diwatas also vary in terms of their powers, importance, and influence over the physical world. Some of these diwatas are believed to be creator gods who made the world and everything in it, which includes mankind. Some examples of these creator gods are Bathala from the Tagalogs, Malayari from the Sambals, Gugurang from the Bicolanos, Kaptan from Eastern Visayas, Pamulak Manobo from the Bagobo tribes, and many others.

These creator gods and deities were also believed to have dwelt in a different realm or kingdom, apart from mortal men. Much like how the ancient Greek gods had Mount Olympus, and the Norse had Valhalla, ancient Filipino gods also had a place they called home. This place where these gods lived was often regarded as either the sky or high up in the highest peaks of their lands. But just as the different creator gods differed from people to people, so did these divine realms.

For the Hiligaynon, their supreme creator goddess, Laon, resides at the peaks of Mount Kanlaon. For the Ifugao, Kabunian (also referred to as Mah-nongan), along with the other deities, the place they call home is the fifth region of the sky or Skyworld. There is also Ibabawon, where the ruling deities Tungkung Langit and Alunsina dwell, Kahilwayan for Kaptan and his large pantheon of gods, and Kaluwalhatian, where Bathala and the rest of the Tagalog pantheon watch over the world.

In fact, in the Tagalog mythologies, the human souls deemed to be good, go to a place called Maca, which is separate from Kaluwalhatian, where the gods dwell. The concept of Maca is actually closer to the Elysium Fields in Greek mythology than to the Christian heaven.

The concept of an underworld where the souls of the wicked are taken, also existed in ancient Filipino beliefs. But unlike the Christian concept of hell, where the biblical devil rules with evil demons serving as his minions, the underworld in Philippine mythology, just as it was with Maca, is more akin to Tartarus from Greek mythology. It is a place where the evil are taken, but those who preside over it are not necessarily evil. It is simply a place where souls are judged and punished accordingly. The deities who usually preside over the fate of human souls are merely doing the task they are meant to do.

Different diwatas from various peoples preside over the Filipino underworld. Some serve as judges, others as ferrymen who guide the souls of the dead, while others have mastery over various elements. And just as there are great leaders and chieftains amongst the diwatas in the other realms, so did they exist in the underworld. For the Visayans, the underworld of Kasakitan was ruled by the brothers, Magyan and Sumpoy. For the Tagbanwa, it is the diwata called Taliyakud. For the Manobo, it was the goddess Ibu. And for the Tagalogs, it was Sitan, who ruled over the underworld called Kasanaan.

Aside from these great and powerful diwatas, there were also the lesser deities who created and maintained a single facet in all of creation. Oftentimes, they were the offspring of creator gods as well as the other deities in their respective pantheons. Some deities oversaw aspects of the everyday needs and labors of humanity. Deities like Dumangan, Ikapati, Kalasokus, Bugan, and many others, aided humanity in the planting, ripening, and harvesting of rice. There were also Magindang, the god of fishing, Kedes, the god of hunting, and Ginton, the god of metallurgy.

There are patron gods to whom warriors pray and make offerings to on the eve of battle. Warriors look to deities like Apolaki, Dasal, Batala, and Darago in hopes of garnering favor through victory or an honorable death. And then there are the powerful gods of the celestial bodies and elements. Gods who created the sun, moon, and stars like the three daughters of Bathala, Apo Init, Agueo, Buan, Pandac, Haliya, and many others. Deities who command thunder and lightning, typhoons and earthquakes, like Revenador, Dalodog, Ribung Linti, Linug, and Yogyog. Whatever aspect that affects the everyday lives of the ancient Filipinos, whether it be good or bad, rest assured, they had a diwata to whom they paid reverence.

Idols, aka Anito

Apart from the invisible spirits of diwatas and deities, others were believed to be minor spirits, the spirits of the dead, or ancestral spirits, depending on the ethnic group. These spirits were usually represented as small wooden idols kept around the household. Much like how Christians and devout Catholics have figures of saints in their altars, the ancient Filipinos kept anito idols to pray to and offer sacrifices for health, blessings, and guidance. This form of worship is sometimes referred to as Anitism or the veneration of the spirits of the dead.

Gods in the Alamat Book Series

As I mentioned many times before, the core premise of my books is that they are retellings of various epics and heroes from different tribes and ethnic groups set in a unified literary universe. Though still based on their original epics, I did take certain creative liberties not just to make them more appealing to the modern fantasy reader, but to bring them all together in a way that makes sense. But that wasn’t the hardest part.

The task most daunting, which I admittedly am still working on, is how to bring the different pantheons of gods, beliefs, and creation stories together. Unlike the gods and deities from other cultures, with a handful of specific characters, backgrounds, and relationships, Philippine mythology is absolutely teeming with them. On top of which, they come from different tribes and cultures, which not only increases their numbers, but also overlaps their roles.

I could have simply picked the Tagalog pantheon of gods (which is the most renowned) and designated them as the only deities governing my Alamat universe, but that would have been a disservice to the beliefs of other Filipinos across the country. So, to incorporate as many deities as I could, as well as provide a blank canvas from which I could recreate my Alamat universe, the first thing I needed to do was to take all of their stories and throw them in a proverbial blender.

I needed a universe where there was more than one all-powerful creator god, and I needed to give rhyme and reason to their stories. So I chose to use a hierarchy system amongst the dozens upon dozens of gods, and used that hierarchy to unify the narrative.

Having been born and a somewhat “devout” catholic, the concept of a One True God appeals to me and thus became my cornerstone. In the Tagalog mythology, as documented by the Spanish, the supreme being called Bathala also went by another name, Maykapal. And if you spoke Tagalog and are a practicing catholic, you would know that the name of Maykapal is often used to describe God the Father (ex, Poong Maykapal).

To set up my hierarchy of gods, I needed to put one god above everyone else. So in the beginning, there was Maykapal, and it was He who began the creation of the world by raising the land from beneath the sea. He then created the thirty-six creator gods, derived from thirty-six ethnic groups. I called these creator gods the Dian, another name for deity.

These Dians in turn, created the lesser gods whom I call Poons (also another term for a god) to help them create the world upon the absence of Maykapal who abruptly left them to create other universes. After creating the celestial bodies and mankind, the Dians then fell into a deep sleep, which prompted the creation of the enkantos by the Poons. Enkantos are solid physical beings in the spirit world, but are ironically nothing more than spirits in the physical world. Male enkantos are called anitos and the female ones are called the diwatas.

With this simple concept, which is ironically also complex, tedious, and complicated, I believe I can stitch together all these different pantheons of gods from as many cultures as I could write about, and create a story worth reading. Though it strays significantly from the original stories, since it would be impossible not to do so, I only hope that what I created makes sense enough to be entertaining from a narrative point of view.

As I write this blog entry, I am currently writing the first of three prequel books in the Alamat Book Series. These prequel books cover everything from the creation of the universe, the rise of humanity, the great flood, to the war of the three realms, culminating in the beginning of the Alamat Book Series, Lam-ang. I plan to release each book at the tail end of each milestone chapter in the series, where the last of the three is released just before the final book in the entire series.

I must admit that pulling this off will be a daunting task, to say the least. All I can promise my readers is that I will do my utmost to make it happen, and my darndest to make it worth your while.